AN INTRODUCTION TO

WALKCYCLES using

BASIC KEYFRAMING AND

F-CURVE EDITING

Compiled by Chris Wyatt updated for Maya by Penny Holton

This

worksheet is intended to be an introduction to the animation tools

within Maya. It will cover basic key framing and the editing of the resulting

function curves in the graph editor.

The

basis of the exercise is a simple walk cycle using a provided Moom utilising

both Forward Kinematics and Inverse Kinematics. It will describe how to breakdown motion studies and principles of walk mechanics from traditional animation into workable layers of animation within the software. This means you can get one element of the walk working before moving on to the next.

THE BASICS

Before we start animating I want to take you through some basic Maya and Moom setup and keying information.

Check your playback fps (frames per second) is correct. For PAL we need 25fps so we can set that manually in the time slider and playback preferences:

HOW TO SAVE KEYS IN A SINGLE AXIS

STEP 1 Left click on the timeline and move to the required frame.

STEP 2 Select a control and translate or rotate your character to the requires position (in 1 axis)

STEP 3 Save a key by right clicking on the selected transformation in the channel box and selecting Key Selected. When keyed the box containing the numeric value will turn red.

STEP 3 Save a key by right clicking on the selected transformation in the channel box and selecting Key Selected. When keyed the box containing the numeric value will turn red.

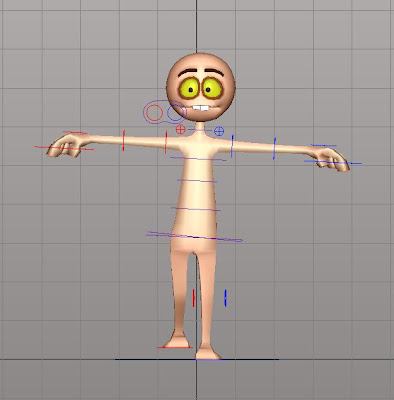

USING MOOM

In this tutorial we are animating his arms in FK, so make sure you switch his arms from IK to FK before starting to animate. Moom has one arm set to IK when he is imported.

Select the L at his feet and change the arm switch control from IK to FK

Watch out for Pole Vectors!

Moom's pole vectors are positioned in front of his knees so we need to move them and save keyframes for them so that they stay in position. If we do not do this his legs will twist as the walk moves forward .. like this.

NOW ON TO WALKS

The image above shows the main components

of one cycle of a biped walk. As covered in your lectures and in books by

Preston Blair and Richard Williams you will recognise the contact positions and

the passing positions used as the 5 key points in the cycle.

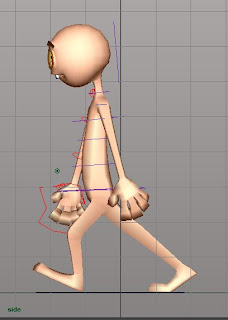

As mentioned above it is best to approach the animation in layers.

The first task is to manipulate your character into the first contact position

at the start of the cycle as shown below. We will save key frames of the key

effectors at this pose as a reference and then begin to animate the first

layer, the hips.

As mentioned above it is best to approach the animation in layers.

The first task is to manipulate your character into the first contact position

at the start of the cycle as shown below. We will save key frames of the key

effectors at this pose as a reference and then begin to animate the first

layer, the hips.

Contact pose

KEYING THE FIRST REFERENCE POSE

To begin pose the character as shown in the contact position. The

hips are almost at their lowest point creating a bend in the leg, the heel of

the front foot is touching the floor and the back foot is just about to leave

the ground. To position the feet use the foot controls to move the leg IK into

place. The look of these controls can vary from rig to rig. In this case they

are shown as foot shaped curves.

Other more detailed rigs may have control objects setup in a

similar way. As you will notice the IK works by translating the effector controls and

recording key frames on the relevant parameters. There are no key frames

applied to the bones themselves only the effector controls. FK rig controls are used to rotate the bones.

So, to reprise the basics, position your hip control and the two IK foot controls in the

desired position at frame 1 and record translation key frames when you are

happy. To do this ensure the timeline is in the correct position, select the controls

and make the change in the required parameter (translation in Z for example)

and record that change by right clicking on the Key Selected button in the

animation controls in the channel box

When you have placed a key frame the button will go red to

indicate this. You can see that on the rotation buttons the key

frame button is not red indicating no animation is present and you recorded a

translation key frame only.

When you have placed a key frame the button will go red to

indicate this. You can see that on the rotation buttons the key

frame button is not red indicating no animation is present and you recorded a

translation key frame only. LOWER BODY

TRANSLATION OF THE HIPS

The first layer to record is the translation of the body forward.

As with most movements of the body this originates at the hips. So we need to

record the general movement of the hips forward first. To do this, select the

hips and move them forward to see where the body may be in the next step. As we

have not advanced the time yet the character will return to the pose so don’t

worry about the strange movements of the legs this is just to get a feel of the

displacement. The feet will be inclined to remain where you key framed them at

frame 1 and will drag behind but don’t worry we will work on the feet later.

As we will keep this cycle to a workable 24 frames you can change

the duration at the bottom of the screen to 24 frames by keying in the frame

numbers in the end frame window. We will be keying the contact positions at

frames 1(already done), frame 12 and returning back to contact at frame 24, in

other words one cycle.

We will key the position of the hips now to anticipate these

steps.

You can start by advancing the timeline to frame 12 and

translating the hips (in Z) to the next contact position and when happy save a

key frame as before. Then you can advance the timeline to the end frame (24)

and again move the hips and save another key frame to complete the full

translation of the hips forward for the cycle. You could however just key the

points at frame 1 and 24 if you felt confident about it. At this point your

character will be in a position similar to below. It looks funny but go with it. All will soon become clear.

You can start by advancing the timeline to frame 12 and

translating the hips (in Z) to the next contact position and when happy save a

key frame as before. Then you can advance the timeline to the end frame (24)

and again move the hips and save another key frame to complete the full

translation of the hips forward for the cycle. You could however just key the

points at frame 1 and 24 if you felt confident about it. At this point your

character will be in a position similar to below. It looks funny but go with it. All will soon become clear.

If you playback your animation you will see that the movement is

from start to finish but is at an uneven pace. The character starts off slow

and then builds up speed and slows to a stop. The key frame in the middle of

the cycle and the way the key frames are interpolated within the software

causes this. This is where the Graph Editor comes in and this basic

translation is a good introduction to this useful tool.

The motion of the hips will be irregular in a walk but for a cycle

it needs to be constant from point A to point B. The animation editor can make

sure of this constant speed. The detail and nuances of this movement can be

added later.

To open the editor in the tip menu go to Window/Animation

Editors and choose Graph Editor.

The Graph Editor shown here simply displays the

displacement (or change) up the side plotted against time along the bottom. The

key frames themselves are displayed as points with the curves plotted in

between them.

As you can see the two key frames of the start and end are

displayed below. If you saved the one in the middle it would be displayed in

the curve. For ease of use I have just used 2 key frames at frame 1 and 24 as

shown below. If you had keyed the hips at frame 12 you could remove it by

simply selecting it by clicking on it and pressing delete.

You will notice that the interpolation of the software plots the

information between the two points as a curve. This is the default and is the

reason for the slow start and slow finish as the curve eases in and out of the

change in value. The hips are not moving from A to B in a constant and linear

as the crow flies fashion but in a gradual manner. This graphic display of the

displacement shows that the steeper the curve the greater the change in

displacement and therefore a flat plateau would represent no change at all.

As you would expect a straight line between the points would

ensure this was the case and that is the first bit of curve editing we will do.

To change the curves

interpolation simply select the key frame at 1 on the graph and it will go yellow

to indicate this, then press the linear interpolation button at the top of the

editor to make the curve become linear between the selected point and the next

one as shown in the following screen grab.

You feel that the motion of the hips is too fast or too slow you

can alter it in two ways. The first way is to do it is to advance the timeline

to the final frame and reposition the hips so they have not advanced as far and

resave the key frame. The second is to select the key frame itself on the curve

and move it down to reduce the value of the key frame at that position on the

timeline, as in other packages you can keep this movement snapped to the

vertical position by pressing shift when moving the frame down.

Once the hips are at a suitable speed you can begin to block out

the position the feet correctly for the second layer of animation.

BLOCKING OUT THE FEET POSITIONS

The next stage is to roughly block in the positions of the feet.

These need only be done at the contact positions at first. For this example the

contact positions are on frames 1, 12 and 24.

The first positions at frame 1 are already done so all that

remains is to key the feet at frames 12 and 24 as shown below. Do not worry

about the roll of the feet as they pass through the floor, as that will be

fixed later.

Once you have blocked out the feet play back the animation or

scrub through the timeline to see the effect

ADDING RISE AND FALL TO THE HIPS

With the feet blocked in we can add the next stage of the

animation. This is the rise and fall of the hips through the passing position.

At the passing position the standing leg is almost at its straightest position

and therefore the hips are nearly at their highest.

Key frame the height of the hips at these passing points by

selecting the hip and scrubbing through the timeline until the hips are over

the feet (or slightly before) and then raising the hips in the Y-axis and

recording a key frame. As you will see the feet stay rooted as they are

animated but the hips move up and straighten the leg out. Repeat this for the

other passing position to complete the highest points of the hip.

That would be fine but there is one more detail to be

reflected in the hips rise and fall and that is that the hips are actually at

their lowest when the figure is in the down position. This is when the weight

is transferred onto the front foot and it slaps to the floor. It is one or two

frames after the contact position. You will now need to save this change at the

relevant frames. You can leave the key frames in as a guide or you could remove

them and alter the curves to correspond by adjusting the bezier handles that

protrude from the points on the graph. The two versions of this detail are

shown in the grab below.

While

we are here we can also add the highest point of the move which is just after

passing position by again adding a key

or manipulating the curves.

ADDING TWIST AND TILT TO THE HIP

When the character is walking the hips also twist and dip with

each step. Your reference materials will indicate when and to what degree this

occurs but usually the hips twist forward with the front leg and also tilt down

towards this foot at the at the contact position.

Firstly key in the rotation with the swing of the legs. This is

done in the contact positions on frames 1, 12 and 24 in this example. To record

the rotation go to one of the relevant frames and select the hips and then

rotate the hips so the root of the front leg is moved closer to being over the

front foot and the root of the back leg moves closer to being over the trailing

foot as shown below. Then when you are happy; save a rotation key frame. Then repeat these steps

for the other contact positions (reversing the twist for the appropriate steps)

The next step is to key in the relevant dip in the hips at the contact

positions. This is done in much the same way as the previous step but of course

the rotations are in a different axis. With the hips selected scrub through the

timeline until the contact position frames. Then at those frames rotate the

hips to dip down towards the front foot. Then as before record a rotation key

frame when the hip is at the correct angle in the front view as in the

following screen grab.

Once the hip dips and rotations are keyed the next part of the

lower body animation is the adjustment of the feet.

ADJUSTING THE FEET

The final steps of the lower body are the feet refinements. The

most obvious errors are the positions of the feet in the passing positions.

These are the first areas to approach. Select the leg effectors and scrub

through to the relevant frames and position them to accommodate the lift of the

foot and record a translation key frame as shown below. Remember that

the lift of the foot will indicate a lot about the characters weight and

demeanour so pay attention to its take off. It could lift fast and far off the

ground and come down slowly or come up slow and slap down fast. Usually we miss

the floor by very little when walking (and some people drag their feet) but if

you do not get it right at first you can change it in the graph editor as

before.

Positioning the

lifted foot at the passing position

The images above show the foot as it hits comes into contact with

the ground heel first at an angle. The image on the left shows the foot slapped

into the down position only two or three frames after the contact to result in

a firm slap onto the floor. This could be really abrupt if the time from the

contact to down position was only one frame and would look odd if it was

slower.

ADDING WEIGHT SHIFT

When the character walks the weight will shift over the supporting

foot to maintain the centre of gravity and balance. You may wish to refer to

the Richard Williams image below as a guide to the positions of the hips

and shoulders as the weight of this heavy character shifts.

You

will notice the shift of weight at the passing position for this larger

character shown in red. To include this in your animation simply scrub to the passing

position frames and add a slight change in translation in X and record

the change with a keyframe. Repeat this for all of the passing position frames.

ADDING FEET SPREAD

Also on the image above you will notice that the feet are spread

out to disperse the weight evenly and stabilise the body. As you can imagine

this is easily added to your walk by rotating the feet outwards at the desired

frames. You may find it more helpful to record this change on the contact

positions first. You may need to add further rotations when your feet are

travelling through the air depending on your character

ADDING OUTSWING

TO THE TRAVELLING FOOT

As well as the feet being parallel and in line in their

orientation they are also in line in translation.

As with the rotations this is incorrect and looks too robotic and

regular. What actually happens is that the feet will swing out as they pass

through the air.

This will be different from character to character but the images

below show how this will be added in this walk.

The existing animation has the feet with a constant x value so

they remain in line as shown by the arrow below.

You already have keyframes stored for the position of each foot on

the contact positions so you need to scrub through to the passing position to

make the changes.

When the timeline is at the desired

frame simply translate the ankle effector out a little in X and save a

keyframe. Once these changes are added and final refinements are made specifically for your character you can move onto the upper body animation

THE UPPER BODY

With the lower body almost complete apart from a few timing and

detail changes the upper body can be animated. The upper body will counteract

the lower body as the image below, taken from a recommended book on the

provided reading list, The Animators Survival Kit by Richard Williams illustrates.

The key points of contact and pass are

shown. It shows the key positions of the shoulders and arms in relation to the

legs in a typical walk cycle. This section will briefly cover some of the key

poses in the upper body of the BASIC walk cycle and introduce the secondary

motion technique in animating realistic movements in your character.

As covered in the lower body section we have

the key positions of the hips in place. Your hips should resemble the positions

in the first diagram or those of your studied walk cycle. Again I will

emphasise that observation and understanding are crucial to successful

animation. If you are unsure about the best way to record key information then

read the book by Richard Williams listed earlier as it is an essential text for

any animator. He also mentions that no two walks are the same so trust your

observations and animate what you see not how you think it should look.

ADDING ROTATION TO THE UPPER BODY

The motions of the upper body in a walk are

mainly to provide thrust and to counter the lower body and maintain the centre

of gravity and balance.

The first step is to put in the rotations or twists of the body that give the shoulders their positions that counteract the hips. It is a good idea to check if your hips are ok at this point.

he shoulders should be in a position that is

opposite to the hips at the point of contact/down as in the diagram so the

first set of key frames will all be stored at these positions in the timeline.

We must save the rotation on each part of the upper body in succession that

accumulate to the full twist of the shoulders in relation to the hips. The

twist will be at its most extreme at the shoulder section but in the parts

below smaller rotations are stored that gradually twist from the hips up to the

full extent of the twist at the shoulders. So to save the first position go to

the first contact pose and do the following.

Select the first spine control above the hips

and save a rotation Key frame that is a

little towards the desired position of the shoulders. Then select the next part

spine control away from the hips and repeat the process. Do this on each part

adding a little more rotation on each part of the spine until the shoulder

section. When the rotation of this part of the body is key framed the

cumulative effect of all the rotations results in the full twist as desired to

oppose the hips.

When all of the rotations are keyed on the spine the effect should

clearly oppose the rotation of the hips as illustrated.

Progressive rotation of spine and shoulder controls

Once you have stored the twist on this contact position advance

the time line to the next contact position and all of the others and repeat the

process. Remembering that the twist should oppose the twist of the hips at that

point.

Once the full extremes of the shoulder twists

are stored play back your movie and you should see that the software has

interpolated the in between frames smoothly which is correct but the shoulders

do not tilt to counter the motion of the hips. The next step is to rectify this

by adding the shoulder dips in the same way as the twist but the rotations are

now in the z-axis.

As the diagram shows the forward shoulder is

the lowest and the trailing shoulder is high. So to save the first shoulder dip,

do the following:

Put the playback head to the first contact

position and select the lowest spine control again.

Then rotate the upper body from this object a

little towards the finished rotation of the shoulder dip and save a key frame.

As previous with the twist repeat this process through the whole

of the torso adding a little more rotation at each section until the full dip

is achieved on the shoulders. The following grab shows the gradual addition of

the dip to each body section.

You may wish to refer to the Richard Williams image below

as a guide to the positions of the hips and shoulders. You will notice the

shift of weight at the passing position for this larger character. I have not

included this for this worksheet but you may wish to add a slight change in

translation in X to your hips at the passing position, especially if you have a

weighty character.

Once the twists and dips have been added to the shoulders there is one more rotation set that is needed to be added to the torso and that is the lean in the walk or the curve of the spine.

This is done as you might expect by adding gradual rotations to

the X axis of each segment of the torso in turn, in much the same way as the

others. The lean forward is on the down or contact frame and the torso will

return to upright near the passing position or slightly after. Do these

incremental rotations in a similar way and save your work.

Nb. Don’t panic . This grab was taken at a later stage

with partial animation of the arms.

I have done all of these rotations in steps for ease of

application and to demonstrate that all of the movements, even a twist of the

shoulder, originate at the hips and must pass through the whole of the body.

This still does not look correct and is a little rigid but this will be rectified with the introduction of secondary motion later.

THE ARMS

THE ARMSThe next obvious step is the positioning of the arms. As mentioned earlier the arms counteract the position of the legs in that with the forward leg approaching the ground the arm on the same side of the body is swung at its furthest position behind the body. This is best illustrated in the diagram on the first page from Richard WIlliams.

To animate the position of the arms in the

most basic way you must do the following.

Select Moom's upper arm bone then

rotate the arm into the desired position. Then save a key frame.

I have advised you to save the key frames in a single axis only

for now to keep track of which key frames have been saved. This is fine for 2D

joints but I am sure you are aware that the shoulder is a 3D joint and

rotations in the other axis’ can be applied to get the correct position. These

changes can be applied later once the basic rotations are done. As stated before; it is a good

idea to work on a per axis approach to saving key frames to keep a clearer

picture of your workflow until you are confident in the animation editor and

other methods.

Record the positions for BOTH arms at these

key contact points, 1, 12 and 24 on the timeline for the duration of the

animation to almost complete the walk cycle.

Obviously the last parts of the hierarchy of

the arm extremities is the forearm, hand and fingers but we will do these

shortly so leave the arms as they are for now.

THE HEAD

The last part of the BASIC animation of the upper body is the head. The head will nod back and forth as the body moves so key frames need to be saved at the positions of the extremes of this motion.

The head is fully nodded forward just as the

body begins to rise back up after the down position and is upright and even a

little cocked back at the up or passing position.

.

ARMS AND SECONDARY MOTION / (OVERLAP AND

DRAG)

You will notice that the animation resulting

from the steps above is ok but it is a little stiff and unrealistic. This is

due to the basic steps we saved and saving them all at the same time.

This is incorrect, as the body does not move

that way. For example when the lower spine rotates in a bend over it moves and

then the mid part moves after the influence of the lower area on it then the

chest then the neck and then the head. This movement continues when the motion

is moving back to the starting position. The stomach moves back then the plexus

then the chest and then the neck and head. This resulting action has a sort of

snaking effect or secondary motion.

Perhaps it would be better to show this with

an example. I will use the arm and its movements in this walk.

Firstly we will need to get the arm and save

key frames for the upper or bicep movement. This was done in the section above

so that is ok.

The next step is to focus on the movement below the elbow relative

to the upper arm.

Now

we need to create the more realistic secondary motion/overlap. To do this we

need to understand that the upper arm will move first and then in turn the

lower arm will move slightly afterwards and as a result the hand will move

after the forearm and so on.

So

if we notice the point when the upper arm has reached the extremity of its

forward movement and begins to move back then we will save the first rotation

of the forearm a few frames afterwards. This is the extreme of the forearm

movement and the arm will be at its fullest bend. This is because its extremes

of action are as a result of the motion of the upper arm and are therefore

slightly offset or delayed in time. This delay is caused by the weight of the

hand swinging on past the elbow when the elbows forward movement has been

arrested or changed direction. In this example it is 2-3 frames as the key

frame for the forearms rotational extremity is now 3 frames after the upper arm

begins to move back.

Next

we need to add this effect to the other extremity of the upper arms movement.

To do this first locate the position where the arm has reached it full rotation

behind the body moving back and note the time. Now we need to select the

forearm bone again if you do not have it selected and save the relevant

rotation key a few frames afterwards. This is to show that the upper arm has

moved and its action will effectively drag the lower arm with it and out of its

current path as a result. This will occur a few frames after and in the example

below the desired rotation is saved 3 frames after the upper arm moves.

The

extremity of the lower arm is saved three frames after the upper arms movement

change.

This can now be applied to all parts of the character from his

hips right through the torso to the tip of his nose. It can be used to give

your character more vitality and spring and also indicate the nature of his

body construction.

CREATING A CYCLE

Ok, we have two steps. Now we need to create more steps without

having to animate them. The aim is to have the character walking through the

scene in a forward moving cycle.

In Maya there are different ways of producing a cycle. For this

example we need cycle and cycle with offset

Those elements that progress the character forward such as the hip

translate in Z and the foot translate in Z need to be cycled using cycle with

offset.Other elements such as the rotations and translations in Y or X can be normal cycles.

To create the cycles select the animation curves and choose either

cycle or cycle with offset.

Create 100 frames and do a playblast.

hmm

hmm

If your walk starts to deviate you

might want to look at this check list

1. Do you have a key frame for each element at 1, 12 and 24?

2. Are the values the same at the start and end of the cycle ?

3. Are the stride lengths the same? any differences will be compounded as the timeline grows.

Check that your distances are the same at each step and your hips are at the same position relative to the feet. You can see

in this example there are differences in both the stride length, hip position and the arm

cycle.

Fixed

BAKING THE CYCLE

If you look at the graph editor you will just see one cycle which is not much use if you want to add additional animation and create variety in your walk. So there is one more thing we need to do and that is Bake the cycle.

First you need to select the curves you wish to bake in the graph editor

Next go to Curves / Bake Channel and select the options box by clicking the square.

Make sure both unbaked keys and sparse curve bake are selected.

Click Apply

Check that you have the right number of frames in the end time box

Click Bake

your curves should look like this

As mentioned at the beginning of this worksheet this is an introduction to walks and F-curves. It provides the basic framework to complete a cycle. It is up to you to plan your animation and add your personal touches to your character. What must be emphasised is the importance of good observation and analysis of your subject matter and the use of traditional reference material.

Also the ability to breakdown an action into various stages or levels of detail will prove helpful when animating. As you have seen from this example detail and refinements can be added at any point to improve your work.